A Different Kind of Holiday Guide: Coping, Connecting, and Finding Support

Written for NAMI Colorado Springs by Rayna Serrato We often think of the holiday season as a time to give,

Written for NAMI Colorado Springs by Rayna Serrato We often think of the holiday season as a time to give,

Did you know that only about 50 percent of people with any mental illness received treatment in 2024? Finding mental

Every week — for adults, at least — work takes up a huge portion of our waking hours. And those

Mental health needs daily, proactive attention … and you can engage in simple ways. Here are some ideas you

Summer’s winding down, backpacks are making a comeback … and as the school year begins, so does a mix of

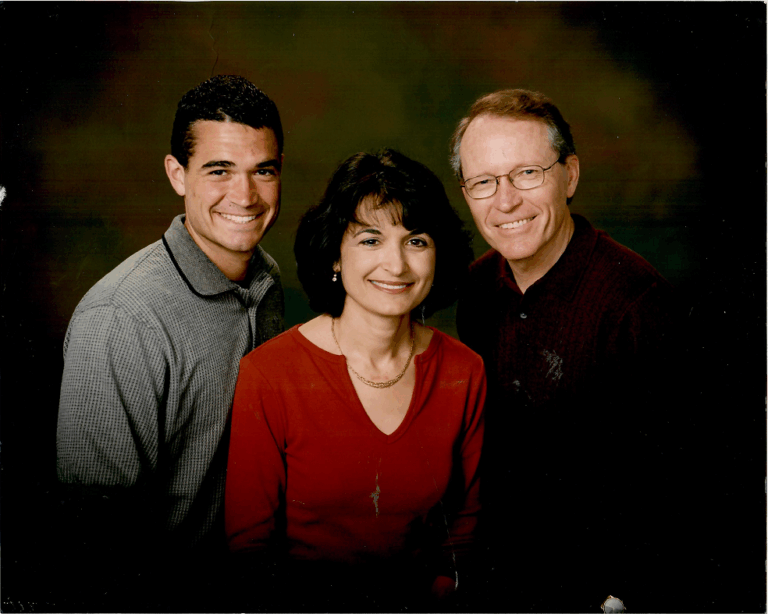

When Mike and Phyllis Foraker sat down to write Mental Health Crisis: The Story of William Foraker, they were writing

When a loved one faces mental illness, it can feel like the ground is shifting under your feet. You want

For anyone facing mental illness, there’s one important factor that we should always embrace: human connection. When we feel seen,

After nearly 15 years of transformative leadership, Lori Jarvis will retire as executive director of NAMI Colorado Springs at the

Meet Dee Menard and Felicia Embry, peer participants in the mental wellness programs at NAMI Colorado Springs.